We've been climbing in seventh grade. Metaphorically, as we scaled the heights of the school year, but also literarily, as we ended the year with a reading of

Peak, by Roland Smith, and then a supplementary non-fiction Everest account,

Within Reach, and

this video story about an expedition that flew a hot air balloon over Everest, so we could get more insight into stuff like how noisy the streets of Kathmandu are, what yaks look like and how a Gamow bag works. (I also read

No Summit Out of Sight, by Jordan Romero, but didn't have time this year to share that with my students. Next year I might swap it in for the other one, because I do like the idea of comparing a fictional account with a non-fiction one, and Jordan is closer to my students' age than Mark Pfetzer, who wrote

Within Reach.)

I'm not sure why I have, in the past few years, developed such an interest in Everest. It's not because I want to climb mountains. I'm scared of heights. I can hardly read about the ladders in the Khumbu Icefall without covering my eyes. I get breathless and shivery as I go through these adventures vicariously. Plus, it's

expensive to climb Everest. Even if I had that kind of money, there are so many other things I'd do with it.

Partly it's because I've fallen in love with Nepal. I've never been there, but I feel as though I have from all the books I've read. We were reading

Peak in

April 2015 when the big earthquake took place there. At that point my students remembered our 2010 earthquake very well, and they, and I, were struck hard by the event. We read articles together and lamented what those people were going through, and my kids had a bake sale to raise money, which they sent to a high school friend of my husband's who was working in Nepal. The accounts I read (and they were many) sounded just like ones from Haiti, except that in Nepal it was cold; my students and I couldn't imagine. I cried, imagining.

Probably it's mostly the metaphor. Everest is the ultimate symbol of an almost unattainable goal.

George Mallory is famously supposed to have said, when asked why he wanted to climb the mountain, "Because it's there." But cavalier as Mallory was about it, plenty of people have not come back from their attempt to summit. Mallory himself was one of them. He disappeared during his climb in 1924 and his body was found 75 years later, in 1999. There are about 200 dead bodies still on the mountain, lying where they fell, still dressed in their brightly colored climbing clothes. Because of the cold, their corpses don't decay. (Here's more of

the "gruesome truth" about that.)

In addition to being difficult, climbing Everest is about preparation, about sitting around a lot waiting for things to happen, and about being stopped by circumstances completely outside your control. You're only on the summit a few minutes; those few minutes are fueled by years of fund-raising, exercising, acclimatization, and scaling lesser peaks. And chances are good you won't make it at all. You might not get there because of sickness, someone else's foolishness, political upheaval, frostbite, bad weather, or dozens of other problems large and small. One guy in

Within Reach dropped his mitten and couldn't get it back; that put an end to his summit attempt.

Sounds like life, doesn't it?

(Also, in climbing as in life, you definitely won't make it without other people's help. These books and the video all explore the role of the Sherpas, who work harder than the climbers from outside for less recognition.)

Early in our reading of

Peak this year, we read

Irene Latham's poem "The World According to Climbers" in

The Poetry Friday Anthology for Middle School as our poem of the day (we read four poems a week, Monday through Thursday, and then listen to a song together on Fridays).

Could it be that there's a middle school English teacher who doesn't have this book yet? If so, you should really go order it right now. I'll wait.

The World According to Climbers

by Irene Latham

They place their trust in a firm

handshake, steel-toed boots

and hats with wide brims.

Rope fibers groan as they cling

like beads of dew on mutton grass.

They don't lament the lack of wing,

only the fact that they can't fly

without them. They forget

why,

shift their focus to

how.

They carry on. There is no

such thing as tomorrow.

Irene's poem became a touchstone for us as we continued to read the book. I would often say, or one of the students would, "Hey, that reminds me of 'The World According to Climbers.'" An example is when Peak's mom tells him, in a somber call on a satellite phone, that he has to become selfish to succeed in summiting Everest. If he doesn't focus, he won't make it. She explains how she had to give up climbing because once she became a mom, she found her focus divided. (And

that's a class discussion waiting to happen!) We talked about how climbing happens step by step.

The PFAMS suggests asking, "What risks are worth taking and what risks are not?" Everest puts that question front and center, but my kids face risks in their lives in Haiti all the time. In some ways, they are far less sheltered than American kids their age, living in a country with few safety features. In other ways, they are super-sheltered, at least some of them - check out

this post to see what I mean. Talking about risk is always an interesting thing with these students.

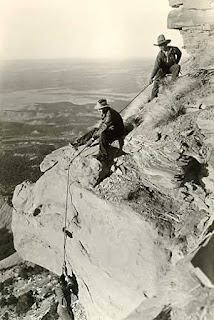

I wrote to Irene and told her what her poem had come to mean to me and to the class, and she wrote back with some more background. She sent me the photo she used as inspiration when she wrote "The World According to Climbers."

She was writing poems at the time using photos of United States National Parks. (This one is from Mesa Verde National Park.) She intended to put them in a book but never found a publisher. She also said that her brother used to be a climber, "so I watched and worried and marveled over his adventures many times!" (Now he's become a cyclist, which I guess is marginally safer.) My students love it when I tell them the authors we read are friends of mine. Thanks for sharing all of this with us, Irene, and giving me permission to share it with my blog readers, too!

So we made it to the summit of our school year - today is the last day of classes, and we have three half days next week of exams and then all the graduations. In my newly-acquired free time in the next couple of weeks, maybe I'll write my own climbing poem. When you get to the summit of Everest, you have to head back down right away after posing for a few pictures; the human body can't survive for long at that altitude, called the "Death Zone." My mountain is a little less extreme. For right now, I'm just going to enjoy the view from up here a little longer before I head back down to the valley and start gathering supplies and strength to climb again next year.

Here's today's roundup.